Influenza

-

What it is?

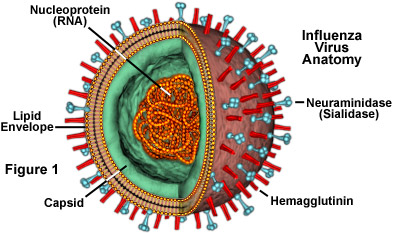

The common cold and influenza (flu) are the most common syndromes of infection in human beings. The mechanisms of symptoms of sore throat, rhinorrhoea, sneezing, nasal congestion, cough, watery eyes, and sinus pain are discussed, since these mechanisms are not dealt with in any detail in standard medical textbooks.

-

Solutions in the USA

Vaccination is the best method for the prevention and control of influenza. Vaccination can reduce illness and lessen severity of infection. This review focuses on how currently licensed influenza vaccines are generated in the U.S., why the biology of influenza poses vaccine challenges, and vaccine approaches on the horizon that address these challenges.

Solutions in the UK

Annual vaccination against influenza is well established in the UK. The traditional vaccination strategy has been to target groups at higher risk of severe disease following infection, such as adults and children with underlying chronic medical conditions; pregnant women; and older people. Although this approach has been shown to be highly cost-effective, a significant burden of disease remains because influenza continues to circulate in the population with a significant proportion of at-risk individuals remaining unprotected due to a lack of vaccination or limited response following vaccination. An alternative approach is universal vaccination offering vaccine to healthy children.

-

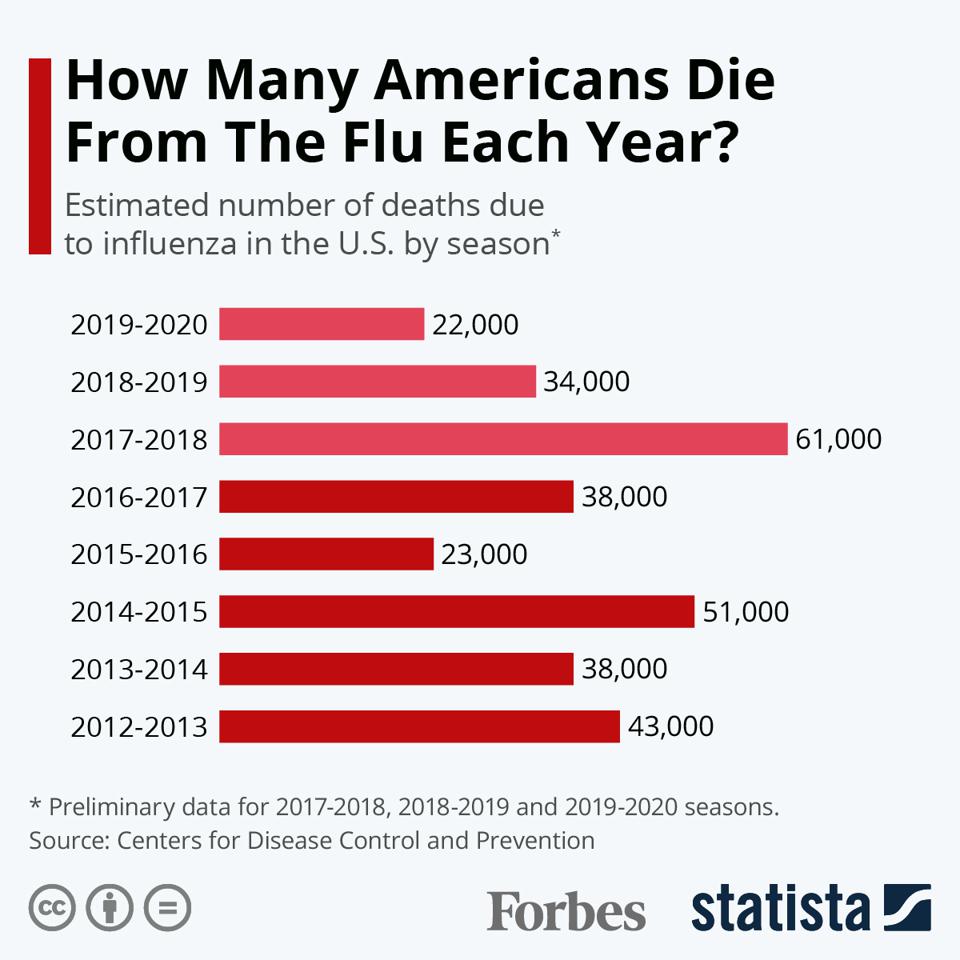

Statistics in the USA

For the years 1933 through 2004, the resident population of the continental United States was used, with the populations of Alaska and Hawaii added from the years they became states (1959 and 1960, respectively). Monthly influenza death rates were calculated per 100 000 population on an annual basis. Influenza death rates in the United States substantially declined across the 20th century, in line with the simultaneous decline in the mortality burden from most infectious diseases, often referred to as the “epidemiological transition. In particular, influenza death rates dropped sharply around the end of World War II (1944–1945).

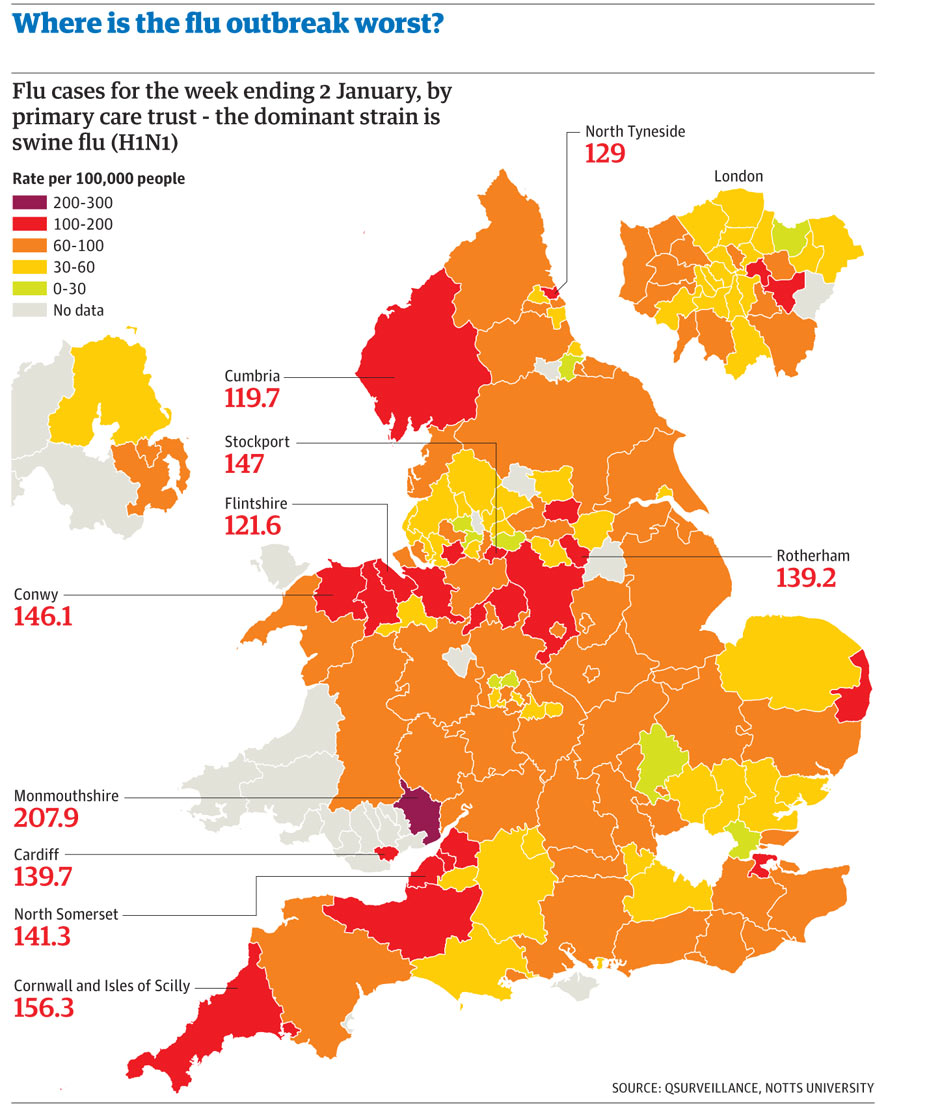

Statistics in the UK

In the United Kingdom there were 28,516 hospitalisations and 7163 deaths estimated to be attributable to influenza respiratory disease in a mean season, with marked variability between seasons. The highest incidence rates of influenza-attributable hospitalisations and deaths were observed in adults aged 75+ years (252/100,000 and 131/100,000 population, respectively).